LITTLETON, W.Va. — In the summer of 1918, a procession of billions of ravenous "worms" passed through the hills of eastern Wetzel County, spreading disorder wherever it traveled. Some who saw it claim to have been attacked in the march. Others claimed to have lost crops and, seemingly, cattle.

Wetzel County worm invasion shocks residents

Thanks to the Internet, such events are more widely known today, but at the time, the march of worms was nearly apocalyptic. The following was recounted in the Fairmont-West Virginian newspaper on July 13, 1918.

WORM INVASION!

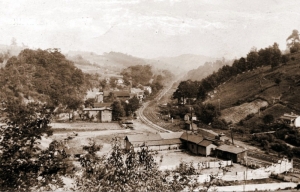

A huge mass of large yellow worms, said to be not less than three miles long and 100 yards wide, is crawling toward Littleton in Wetzel County, West Virginia.

The Fairmont newspapers inform that on Sunday morning, June 31, a well-known county farmer, Milliard McDougal, woke to find millions of worms heaped high against his house. Since then, the worms have hidden many buildings from view simply by crawling over them.

Another Wetzel County farmer, Jim Fox, was forced to stop plowing when the worms attacked him and his horses. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of people from Littleton and elsewhere have been traveling on foot, on horseback, by teams and buggies and wagons, and in automobiles to see the weird worms as they wiggle, stretch, creep, and crawl westward across Wetzel County.

According to a newspaper report, it takes three days and two nights for the worms to wiggle past a given point. The mass is at some places a foot thick. It completely covers the hills, hollows, and level sections over which it moves.

So far, though—and thank the Lord for it!—the worms have done no visible damage. They seem not to eat anything, and some observers believe they are crawling to commit suicide and will pile themselves up and die.

Stock will not eat any grass the worms have crawled across, and chickens will not eat the worms. It is the most profound mystery that has ever occurred in this country. The worms are about two inches long and one-eighth inch in diameter. They are bright, brownish-yellow in color, and they have hundreds of legs, it seems.

Where did the weird worms come from? Where are they going? Will they eventually destroy Wetzel County, as some observers believe?

Read also: Little girl saved train on the little-known Short Line in 1902

A university entomologist, Prof. Peairs, does not know why the weird worms march. He has visited Wetzel County for a first-hand look and says:

"Ordinarily, this type of worm does not venture into open country. It does not feed on any food that people eat but subsists entirely on decayed vegetation, rotting logs, stumps, leaves, etc. It lives in shady, damp places and will soon perish without abundant moisture."

The professor says he never heard of the worms appearing in such great numbers and is at a loss to understand how such a thing could happen. He states that the march of the weird worms is phenomenal and unique and that nothing like it has ever been known in his experience.

The march, however, has finally stopped, and most of them along the way are dead and lying in heaps along the railroad. Prof. Peairs says there is very little recorded information about these worms. Their scientific name, the professor says, is "Polydesmus."

Wetzel County worm invasion culprit

Polydesmus, a genus of flat-backed millipedes, is commonly found across temperate regions, including much of eastern North America. According to millipede researcher Richard M. Shelley of the Virginia Museum of Natural History, these arthropods belong to the order Polydesmida and are recognizable by their flattened, plated bodies and wing-like extensions along their sides.

Typically one to two inches long, Polydesmus species are slow-moving recyclers of forest debris, feeding on decaying leaves, wood, and other organic matter that helps return nutrients to the soil — a process long noted by biologists such as Stephen P. Hopkin and Helen Read in their studies of millipede ecology.

In the humid forests of the Appalachian and Mid-Atlantic regions, Polydesmus thrives in shaded, damp environments beneath logs and stones. Entomologists Paul Marek and William Shear have reported that populations often surge after heavy rainfall, when moisture levels favor their activity.

Though harmless, these millipedes sometimes appear in startling numbers—the kind of natural event that once led to reports such as the Wetzel County worm invasion.

A storied West Virginia monument stands forgotten in the woods

Finding it on a map is difficult. Hiking to it is even more challenging. But on a wooded hillside at the southwest corner of Pennsylvania, a weathered monument establishes West Virginia’s singular northern panhandle. Some say it’s a site that every resident of the northern panhandle and every West Virginian should see. READ THE FULL STORY HERE.

Sign up to receive a FREE copy of West Virginia Explorer Magazine in your email weekly. Sign me up!

I’ve noticed millipedes will “march” in droves during drought, I presume to find damp harborage. I wonder what the precipitation situation was at that time.

"three miles long and 100 yards wide"

That does not sound logical.

Also 1918 and no photographs?